The following text is taken from the Delaware River Chapter of the Traditional Small Craft Association's Mainsheet April and May 2008 issues:

MUSING ON TUCKUPS, part 1

~ Roger Allen

The Tuckup was built at the ‘Workshop on the Water,’ a program and facility that I started in 1979 at the Philadelphia Maritime Museum, aboard a 110 foot by 40 foot steel lighter barge called MAPLE. A lighter barge is like a big floating warehouse, and it made a great shop except that you couldn’t use a level. We bought the barge for scrap value from Independent Pier and Lighterage, a tugboat outfit that had been working on the Delaware since 1870 and literally raised her off the bottom of the river. After power washing and pumping a foot of Delaware River mud out of her hull, we wove galvanized chicken wire and re-bar through her angle iron floor beams and then poured in eight inches of concrete to seal off the places in her bottom plating that had rusted through since she was built in 1947. How about that for a volunteer project? Raising a three hundred ton sunken barge isn’t a job for the faint of heart, and I couldn’t believe that we did it. I say “we” because then, as now, I worked with some really great folks who volunteered to help. That crew really put up with some hard and lean times because we worked hand to mouth most of the time. Money was scarce, and supplies and materials to build the shop and set up the program often came when volunteers were able to “find” something we needed somewhere along the commercial waterfront. It’s always been amazing to me how resourceful a crew can be when they believe in what they’re doing. It’s even more amazing how much work can be done and how much knowledge is out there to bring to bear on a worthy project when you get everyone involved in solving problems. Of course, Philadelphia was one of the most important yacht and ship building and service ports on the East Coast so there was lots of talent and stuff laying around that was “not being used by anyone else” when we needed it. In any case, MAPLE swam on the bottom for well over 18 years and served us well as an all around boatbuilding shop and classroom, floating in a

waterfront park called Penn’s Landing in the heart of downtown Philadelphia. She has been scrapped over the last few years, I’ve heard, but I guess we all end up in the scrap yard eventually.

T he Tuckup that Tom Shephard and the Delaware River TSCA sail was one of three that we built at the Workshop, in 1986 I believe. Barry Thomas, working with Ben Fuller at Mystic Seaport, built another four. By the time of the project I was doing much of the administrative and fundraising stuff to keep things going, and we hired a boatbuilder by the name of John Brady to handle the fun stuff. I taught boatbuilding occasionally, did the exhibits, and raised money, but I don’t think I did much more on the Tuckups than a single plank, a couple of hundred rivets, and a steam-bent coaming. (It’s always been like that, by the way. I build the programs so that I can build the boats but then find out that for the boats to continue being built, I have to do the work of keeping the wolves from the door while someone else comes in to have the fun of building the boats.) he Tuckup that Tom Shephard and the Delaware River TSCA sail was one of three that we built at the Workshop, in 1986 I believe. Barry Thomas, working with Ben Fuller at Mystic Seaport, built another four. By the time of the project I was doing much of the administrative and fundraising stuff to keep things going, and we hired a boatbuilder by the name of John Brady to handle the fun stuff. I taught boatbuilding occasionally, did the exhibits, and raised money, but I don’t think I did much more on the Tuckups than a single plank, a couple of hundred rivets, and a steam-bent coaming. (It’s always been like that, by the way. I build the programs so that I can build the boats but then find out that for the boats to continue being built, I have to do the work of keeping the wolves from the door while someone else comes in to have the fun of building the boats.)

John later built melon seeds with the help of John Tohanczyn, a friend of ours who now runs the SPIRIT OF MASSACHUSETTS, the HARVEY GAMAGE, and one other big schooner out of Maine. Both are giants in this business. Brady left to go out on his own for a while but came back to the Museum a few years after I left and has kept that shop going. John Brady is one of the best boatbuilders in the country and a very talented designer as well. John Tohanczyn is one of the most knowledgeable folks in the business when it comes to big boat care and feeding. Tow, as he is generally called, is one of those folks you want in your lifeboat when the world goes to “Harry in a handbasket.” He is one of the very few folks in the whole boatbuilding world that I’d hand a belt sander to (and for those of you who have known me for any length of time, that is true high praise). All of us who are citizens of the Coast meet eventually, and I’m sure you’ll bump into John or Tow one of these days. You

will be glad you did.

Anyway, I won’t tell you about why we built the Tuckups or about capsizing them for now.

(Those stories and more will be in the May Issue.) |

MUSING ON TUCKUPS, part 2

~ Roger Allen

The Tuckup is a fourth class “Hiker,” and it reportedly originated as a crabbing skiff common to coastal bays in the general vicinity of Point Pleasant, New Jersey (some distance north of Parkertown and Tuckerton where the melonseed first appeared, for those who care about such things). There were four classes of Hikers that raced on the Delaware River from just after the Civil War (locally known as the War of Northern Aggression) until the turn of the century. The classes were all 15-foot cat-rigged sailboats, and the class distinctions were broken down according to beam, sail area, and crew size. The largest Hikers had unlimited sail area with beams that reflected the extremes of the rig. They were easily distinguished from the other classes because the boats required iron spreaders that crossed the deck and extended outward from the rail as much as three feet on each side. Mast heights commonly reached in excess of twenty feet, and without crew the boats would roll over. The boats were called Hikers because ballast was usually crew weight and not actual ballast in sand bags. This was supposedly done because the Delaware River is relatively narrow, and in a race upwind with a lot of short tacks, it wasn’t possible to shift bags often enough to be practical. Thus, the crew was required to hike way out to keep the boats upright.

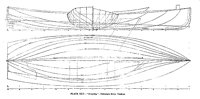

Tuckups were the smallest of the classes, and their name was derived from the shape of the stern, which tucked up into a very pretty shape with a difficult twist of the planking. Stealer planks were occasionally required to achieve the desired tuck, which is a very

interesting bit of work when planking a lapstreak boat. Tuckups were partially decked, lightly built of white cedar planking with steam-bent oak or locust frames, limited to a cat-rigged sail with an area of (I believe) 144 square feet and a maximum beam of (something), and could have no deck spreaders. They carried a captain, sheet tender, topping lift tender, and bailer as crew. Tuckups had to carry the same number of crew throughout the race, something that was not true for the rest of the classes. If the wind looked like it was going to be heavy, you might start out with eight crew members in the larger Hiker classes (mind you, this is in a 15-foot LOA boat hull!). If it shifted to lighter air, you might drop crew over the side during the course of a race. There were lots of what were called “Fishtown tricks” like that in use during the races. Fishtown is one of the waterfront communities within the city limits of Philadelphia. The Tuckup crew did hike out, and generally the boats were equipped with ropes with toggle handles that hooked into fittings bolted through the plank keel. The bailer was the only crew person who generally didn’t hike out and you can figure out why yourself. The topping lift tender was necessary because the boom is so long in a Tuckup that it could hit the water easily and slow the boat, or even bring about a capsize.

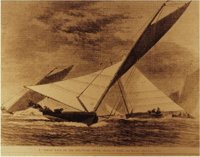

Tuckup and Hiker regattas were big events on the Delaware; large excursion steamers were regularly chartered to carry hundreds of people each as spectators. There are newspaper reports that list upwards of several hundred boats for the various classes, including  Duckers, on a good weekend in the heyday of small boat racing from 1880 to 1890. The shores of the river were almost always lined with spectators as well. There is a famous painting by Thomas Eakins that depicts a race day on the Delaware, and we once tried to count all the boats in it but stopped at over a hundred. The painting is spot-on accurate for detail because Eakins was a keen sailor and boatman, and the painting is a self-portrait of his own victory in a Hiker. Duckers, on a good weekend in the heyday of small boat racing from 1880 to 1890. The shores of the river were almost always lined with spectators as well. There is a famous painting by Thomas Eakins that depicts a race day on the Delaware, and we once tried to count all the boats in it but stopped at over a hundred. The painting is spot-on accurate for detail because Eakins was a keen sailor and boatman, and the painting is a self-portrait of his own victory in a Hiker.

Philadelphia had an egalitarian yachting scene. The boats were raced out of relatively small two- story boathouses that might contain two Hikers, two Tuckups, three or four Delaware Duckers, and a few sailing canoes. Downstairs was boat storage; upstairs was the clubhouse and lockers. The boat clubs might have house painters, lawyers, carpenters, and bankers as members. Unlike elitist organizations in New York and New England, where professional sailors were hired to run yachts during races, boat crews were usually club members in Philadelphia. Boat clubs were arranged in rows down either side of large commercial wharves and piers in specific areas of the Philadelphia and Camden waterfronts, including Bridesburg, Southwark, and Pea Shore. Betting was

one of the big attractions for the races, and competition was reported to be fierce. Boat bottoms were regularly polished and then rubbed with graphite to make them slick. The boats were brightly painted and very fancy according to the records that survive. Chromed fittings and pink, green, or other pastel-colored hulls were not uncommon. story boathouses that might contain two Hikers, two Tuckups, three or four Delaware Duckers, and a few sailing canoes. Downstairs was boat storage; upstairs was the clubhouse and lockers. The boat clubs might have house painters, lawyers, carpenters, and bankers as members. Unlike elitist organizations in New York and New England, where professional sailors were hired to run yachts during races, boat crews were usually club members in Philadelphia. Boat clubs were arranged in rows down either side of large commercial wharves and piers in specific areas of the Philadelphia and Camden waterfronts, including Bridesburg, Southwark, and Pea Shore. Betting was

one of the big attractions for the races, and competition was reported to be fierce. Boat bottoms were regularly polished and then rubbed with graphite to make them slick. The boats were brightly painted and very fancy according to the records that survive. Chromed fittings and pink, green, or other pastel-colored hulls were not uncommon.

The whole culture fairly quickly died out because of increases in port activity, the rising value of waterfront land, and pollution in the river. The bicycle, baseball, and problems with gambling also contributed to the decline. The boats were sailed hard and lightly built. There are only three original Tuckups left in the world: THOMAS M. SEEDS at the Mariners’ Museum in Newport News; SPIDER at the Independence Seaport Museum in Philadelphia; and a Tuckup hull that was built as a rowboat, also at ISM. There is a period  set of plans for a fourth boat, the PRISCILLA I believe, that was published in Forest and Stream magazine back in the 1890s. As I mentioned before (see the April 2008 issue of the Mainsheet), there are replicas that were built in Philadelphia and Mystic and by our wonderful friends John and Vera England in Urbanna, Virginia. Most of the modern boats were built with several complete rigs as the boats are used for racing and pleasure sailing. The all-out racing rig is a scary thing if you are as afraid of the water as I am. It is a big gaff rig!! The smaller pleasure rigs have been built as gaff, sprit, and sliding gunther rigs. The smaller sail makes for a very mannerly sailing boat that can still get out of its own way. Full and complete plans are available for the boats from the Independence Seaport Museum, and John Brady would be a useful resource for anyone who wanted to build a replica. There is a lot of unique gear and rigging details in the plans for the boats too. set of plans for a fourth boat, the PRISCILLA I believe, that was published in Forest and Stream magazine back in the 1890s. As I mentioned before (see the April 2008 issue of the Mainsheet), there are replicas that were built in Philadelphia and Mystic and by our wonderful friends John and Vera England in Urbanna, Virginia. Most of the modern boats were built with several complete rigs as the boats are used for racing and pleasure sailing. The all-out racing rig is a scary thing if you are as afraid of the water as I am. It is a big gaff rig!! The smaller pleasure rigs have been built as gaff, sprit, and sliding gunther rigs. The smaller sail makes for a very mannerly sailing boat that can still get out of its own way. Full and complete plans are available for the boats from the Independence Seaport Museum, and John Brady would be a useful resource for anyone who wanted to build a replica. There is a lot of unique gear and rigging details in the plans for the boats too.

Why sail one now? Because unless you have, you’re not a real man! Unless you have, you’re not a Boatman, or a Waterman, or a complete sailorman. Unless you have sailed a Tuckup, you’re a lubber, and you should keep your eyes downcast when speaking in the company of real sailormen who have. Couldn’t be any better reason than that except that when a Tuckup is cooking along with that big racing rig, it is a most exhilarating sailing thing to do with friends.

|